Designer-Developer handoff: The art of collaboration

When we refer to a ‘design handoff’ we are speaking about the process where designers submit their design prototype to engineers for development. Historically, this process causes some confusion, and issues arise from poor communication and flimsy process management. Even though this is common, it is also easily avoidable. Here’s how.

Rethinking the handoff

The primary cause for confusion is the misinterpretation of the term, and thus the process. It is just that – not a once-off event, but rather a continual process between designers and engineers. A common misconception is that once the prototype is ready for engineering, it is the end of the design work and the beginning of the engineering process. When designers first handover their prototypes to their engineering team, it should not be the first and only time the two departments interact with one another – far from it.

This is a fairly simplistic view of the product development process, and it can hurt the way you approach certain projects such as building an app. When designers handoff design prototypes to their engineering colleagues it must be seen as a collaborative process, rather than something conducted in isolation. Just like any successful team in any department, collaboration is key.

What does this look like?

Often, design and engineering teams work alone and only interact during handovers and iterations. But this is wrong. Design and engineering teams need to be collaborative and work closely together at every step of the development process. Only then they can achieve a successful product delivery beneficial for the end-user.

This entails an engineer sitting at the design desk during the ideation process to weigh in on certain elements and provide guidance on the tangibility of ideas right as they are being created. It also helps the engineering team to have an idea of what is coming so early preparation can be done. This goes both ways – designers should continue to interact with engineers after the first handoff to offer guidance and expertise as and when issues arise. The two departments must operate as a single organism with each understanding as much about the internal mechanics of the other as possible, in order to develop a clear and transparent dynamic.

The same goals

Although design and engineering departments are different, they can be viewed as two sides of the same coin – meaning although they have different processes and targets, they both share the same end-goal: to create a product that serves the user as best as possible. The look and feel of a product are just as important as its functionality and performance.

The best products have an equal share of the load on both design and performance, and products which tip the scale on either side fall short of delivering the best user experience. Thus, insights gleaned from both designers and engineers in the ideation and development phases have equal importance, so clear communication and collaboration between the two are crucial.

Same page collaboration

In order to get on the same page, it is good to remember that after the initial design handoff the process is far from over. Designers may have a much deeper knowledge of the product after submitting it for development, however, issues will always arise once the design is being engineered. Designers know about design, but cannot possibly know all the engineering nuances to make their visions a reality. Some elements may at first appear to be great in the design process but after they have been built, they may either not work as intended, or simply don’t gel with the rest of the design elements.

The point is that a blueprint is not the final product. When the product is being developed the designers must be involved in each step of the engineering process to see how they can adapt their designs when engineering functionality won’t allow aspects of the design to be implemented.

If your design and engineering teams are collaborating in both the design and development processes, then issues can be flagged early on and all creases can be ironed out before it’s either too late or too expensive to change. When engineers are fully aware of the reasoning and approach of the design, they are able to make more informed decisions in line with the design process, especially when some issues arise in the development process. If they are given zero design context, their room for adjustments and manoeuvres in the engineering phase is highly limited.

Communication is crucial

When teams have built a solid foundation of communication then all interactions and collaborations run smoothly – that’s simple enough, right? But often teams work in isolation, which adds far more importance (and room for error) to briefs. When there is a poor communication dynamic between design and engineering teams, simple and often silly mistakes are made which, if not flagged, end up in the final product.

Engineers must feel comfortable to raise concerns or misunderstandings as and when they occur. Designers must be aware that by their very nature engineers do not speak their language, so they must be able to impart their ideas and reasoning in a way that is easy for engineers to understand. This is a two-way street. Engineers must also understand that their field of discipline has a completely different way of working. So both must reach out to one another and try to find solutions to ways in which ideas and thought processes are communicated.

Practical tips for designers

A good starting point for designers is to come from the mindset that their design elements and intended functionality may not be understood as clearly by engineers, so being borderline pedantic in your explanations will help a great deal.

For example, designers often do not inform their engineers about hover effects and how exactly they envision them in the final product. They assume engineers know the concept of hover effects, but any designer will tell you that hover effects come in a multitude of designs and functionalities. Without clear guidance, engineers will see ‘add hover effect’ in their brief and then develop them according to their own ideas. This is where confusion sets in. Don’t make engineers think for you, allow them to see your vision by clearly explaining it to them.

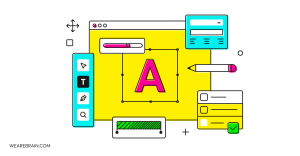

Advice from our own designer, Pavel

According to our awesome Brainiac designer, Pavel, it is important to standardise all objects in the design layout. “If the title is in Open Sans 1.2em, then let it be Open Sans 1.2em everywhere. Do the same for buttons, paragraphs, leading and indenting. I don’t mean that everything should look the same. You should understand that the more typed objects you have, the easier it is for a front-end developer to work with them.”

Pavel also insists on the importance of correctly naming layers and groups, and always observing the hierarchy of elements. Too often front-end developers receive layouts with multiple layers, with no titles, that are chaotically located which of course causes unnecessary confusion. The more understandable the layout is, the faster the mockup becomes an excellent site or application.

Of course, this is also very helpful for designers too. When there are a lot of layers, it’s obviously more convenient to navigate layouts if they are clearly named. “To do this, rename the layers according to their meaning. Use common terms such as button, title, footer and so on in the layer names. Group all the layers that are part of the same component together and follow the sequence from top to bottom. The header should be at the very top, the content in the middle, the footer below, etc.”

If you provide your engineering team with a static layout, try to leave as many comments as possible on the design elements. Try to anticipate any questions that may arise and address them even if they may appear routine and elementary – nobody ever complained about receiving too much detail in a brief! Most interface creation tools make it easy to leave comments for your engineers.

Our designers at WeAreBrain use Zeplin and InVision, for example. Other alternatives are Mockplus and Sympli Handoff.

Practical tips for engineers

It is vital for engineers to try and understand the reasoning behind each design element, so that they are able to suggest relevant alternatives when issues arise or certain elements cannot be built. What is equally important is that this process is done before the build – there is no use in flagging issues after the fact.

By understanding the context behind why a certain image or functionality has been suggested, engineers both keep designers on their toes knowing each design element needs to have a purpose. But it’s also to keep engineers informed enough to be able to take initiative in certain situations during the development process because they have been provided context

Tools and software

Something that should take place before any design has begun is a discussion between designer and engineer as to what tools to work with. If no tools and software to work from have been agreed upon, the result is that front-end developers receive layouts in uncommon formats, which makes it difficult to see the dimensions, colours, shadows or padding. It is therefore crucial that both designers and engineers decide together which program best suits each team. Seeing as the design process occurs before the building process, it is incumbent on engineers to insist on this discussion before any design elements have been created.

When creating user interfaces, us nerds at WeAreBrain like to work with Adobe products such as Adobe XD, and others like Sketch, Figma or Framer.

Summary

The design handoff is not a singular event but a continual process. In order to reduce iterations and misunderstandings, a strong foundation of communication channels needs to be established between design and engineering teams. Although they inherently speak different languages they are working toward the same goal – the user experience – and so they need to work collaboratively at each stage of the process in order to create the best products.

Engineers should be included in the ideation phase right through to the design handoff, and designers should continue to track the build of their designs with their engineering teams in order to create collaborative solutions to problems which often arise during development.

Anastasia Gritsenko

Working Machines

An executive’s guide to AI and Intelligent Automation. Working Machines takes a look at how the renewed vigour for the development of Artificial Intelligence and Intelligent Automation technology has begun to change how businesses operate.